Making space for residential bicycle parking

Processes of transformation in established urban neighbourhoods in Hamburg, Germany

Cycling cities of the future face the challenge of transforming urban space to accommodate cycling infrastructure – this includes residential bicycle parking. Taking the emerging cycling city of Hamburg as a case, I investigate the topic of residential bicycle parking in established urban neighbourhoods. In Hamburg, diverse constellations of actors and varied urban morphological, regulatory, institutional-organizational, and external factors converge to transform urban space in unique ways. By focusing on residential bicycle parking and the key actors responsible for its planning and implementation, I hope to shed light on fine-grained urban spatial shifts and processes at play as this city moves towards a low-carbon, active-mobility future.

- mobility

- bicycle parking

- sustainability in urban space

- transformation

Context

Many cities are setting ambitious goals to increase cycling rates as they commit to transforming their transportation systems towards a lower-carbon mobility future. As one such city, Hamburg aims to double its cycling modal share, from 15% in 2017 to 25–30% by 2030.1 Achieving this goal requires a multifaceted approach, from information campaigns to expanding the cycling network to adding bicycle parking at origins and destinations. Bicycle parking for residences can, in the case of new buildings, be regulated in the building code. This, however, has little effect on existing buildings and their urban settings, where space is limited and uses are well established. Another challenge is that the ideal location for residential bicycle parking often hovers between private and public space, complicating considerations of who should pay and who benefits. On the ground, as diverse actors work in a varied spectrum of urban settings, they also face multiple overlapping layers of regulations. Add to this the evolving understanding of what ‘bike’ parking is for – e.g., e-bikes, cargo bikes, and trailers – and the act of deciding what, where, and how to build becomes even more complex.

Aims

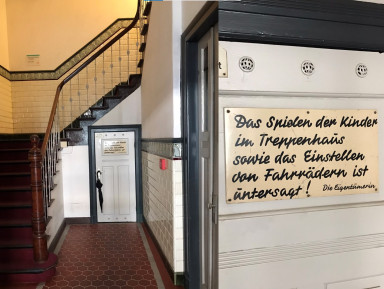

This research project focuses on bicycle parking near the home: residential bicycle parking. More specifically, the spatial focus of this research is on areas of Hamburg with mid-rise apartment buildings, one of the most common housing types in Hamburg. Red-brick or plaster-covered apartment buildings in the inner city are usually four to six stories, are well served by basic amenities – grocery stores, shops, restaurants – and are usually a reasonable cycling distance from workplaces. Most of these buildings were constructed between the 1890s and 1960s, designed during past mobility regimes when parking demands for bicycles were not considered. Today, many residents struggle to find a place to park their bikes that is safe from vandalism and theft, protected from the elements, and easy to access. There are, however, cases in which existing space has already been adapted. Bicycle sheds, bicycle racks, and retrofitted bicycle storage rooms in buildings can be found in a variety of forms across Hamburg, on both public and private property.

The aim of this research is to investigate the ways the built environment is transformed at a micro-level to better understand how key actors navigate the current policy and regulatory landscape, visions of future mobility systems, complex networks of actors, and diverse spatial settings in order to take action, or in some cases, decide not to act. This research will contribute to the growing body of research on bicycle infrastructure and, more specifically, to bicycle parking at or near residences, a topic that has so far seen little emphasis in international scientific literature.2

Research design

The research is organized in two main parts: (1) the case of Hamburg, and (2) a multiple case study investigation of bicycle parking projects. To investigate Hamburg as a case, policy documents and other urban data (e.g. mobility survey data, mapping data, population and housing statistics) are supplemented with data collected in the form of interviews and observations in the field. To better understand the generalizability of the research and place the case of Hamburg in a broader context, I also consider international cases that emerge over the course of the project. The multiple case study of bicycle parking projects uses the level of implementation as the unit (e.g., street section, block, plot). Whereas a municipal planner might be concerned with redesigning a street section to include bicycle racks, a housing association (Genossenschaft) might be responsible for multiple buildings on a city block, and an owner of a single apartment building would likely focus on the scale of the plot. Case studies are selected in a purposive sampling of projects that can be found within urban neighbourhoods and represent different actor constellations, administrative districts (Bezirke), property types, and planning eras. Both successful projects, which resulted in the construction of residential bicycle parking, and unsuccessful projects, in which no construction took place, are included.

Supervisors: